Reproduction of Color Part 1: Physics of Light

I prepared this material to be delivered in spoken form to a mixed audience of game developers. Accessibility is prioritized over precision.

- Part 1: Physics of Light (You are here)

- Part 2: Human Vision System

- Part 3/4: TODO

Most of us deal with color on a daily basis. Color is often a key ingredient for identity, whether that be a character, a logo, or a brand. We will want to choose some specific color, and then reproduce it elsewhere, perhaps in multiple kinds of media.

To do this, we would need to describe a precise color. This is difficult - because color is the sensation of an appearance. How do we precisely describe a sensation? Would a better understanding of how we perceive color allow us to enhance the images we show in a game or in linear media?

Over the next hour, I am going to describe the process of color perception. First, we will discuss the physical processes involved - the nature of light, and the human anatomy that perceives it. Later, we will discuss how we can measure and reproduce color.

We will begin by discussing the physical nature of light.

What is Light?

Our understanding of light has changed radically in the past 500 years. I’m sure many of you already know that light has a wavelength and that wavelength relates to color in some way. Rather than start from a conclusion, I will walk through some key observations of what light physically is. We will use those observations as evidence to form our conclusion.

Isaac Newton (1600s)

Our first observations come from two experiments performed by Isaac Newton.

- First, he used a prism to split “uncolored” light into single-color light. Then, he attempted to split the single-color light again with another prism. He observed that the second prism did not affect the color of the light.

- Next, he split the “uncolored” light again, and then recombined the resulting colored light. He observed that the recombined light looked like the original light, before it had been split.

Newton’s experiments were clear evidence that uncolored light is the combination of colored light.

This ran counter to common belief at the time. Historically, a question like “what is light” was approached philosophically. The prevailing view during Newton’s time was that the uncolored light which “came from the heavens” must be “pure” (because how could anything that came from the heavens not be pure?). So, the prism must be somehow adding color to the light, “contaminating” it.

Newton’s systematic approach of careful measurement and observation is more akin to how we approach science today, and we will continue building an intuition for the substance of light with more observations.

William Herschel (around 1800)

Moving forward to around 1800, William Herschel, an astronomer, was experimenting with colored and darkened glass to allow safely observing the sun. He noticed that when some of these were used, there was a sensation of heat coming through the the lens, and that it didn’t necessarily correspond with the amount of light coming through the lens.

He decided to plot the perceived brightness and temperature of the light coming through the lens. He noticed a clear trend of increasing temperature towards red. He followed this trend, placing a thermometer beyond the range of visible red light and measured even higher temperatures in the “invisible” range.

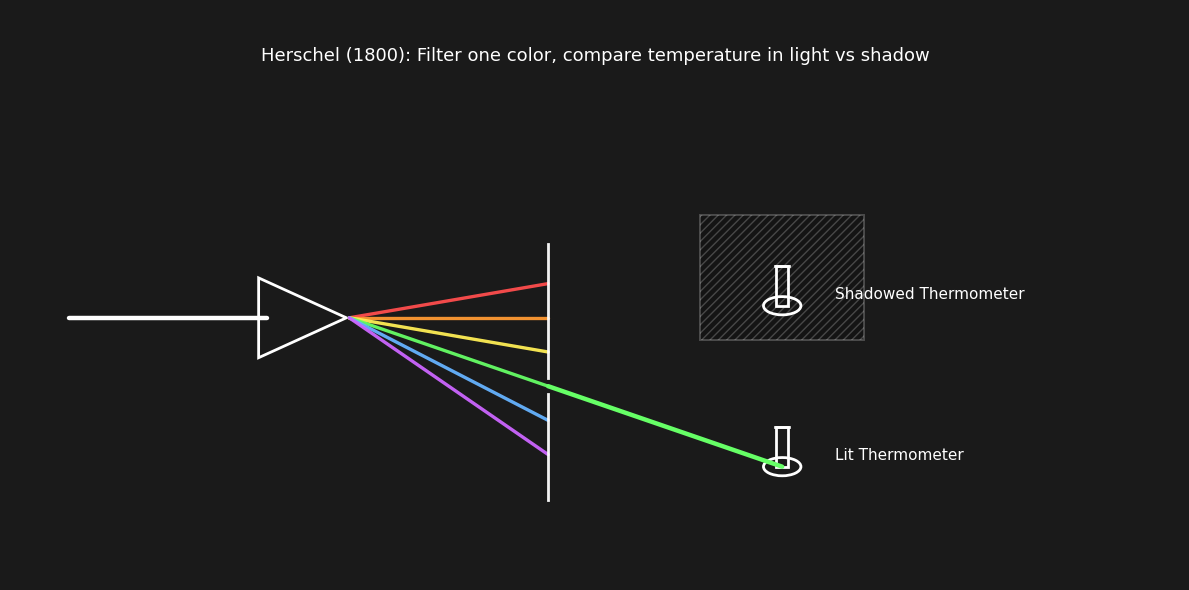

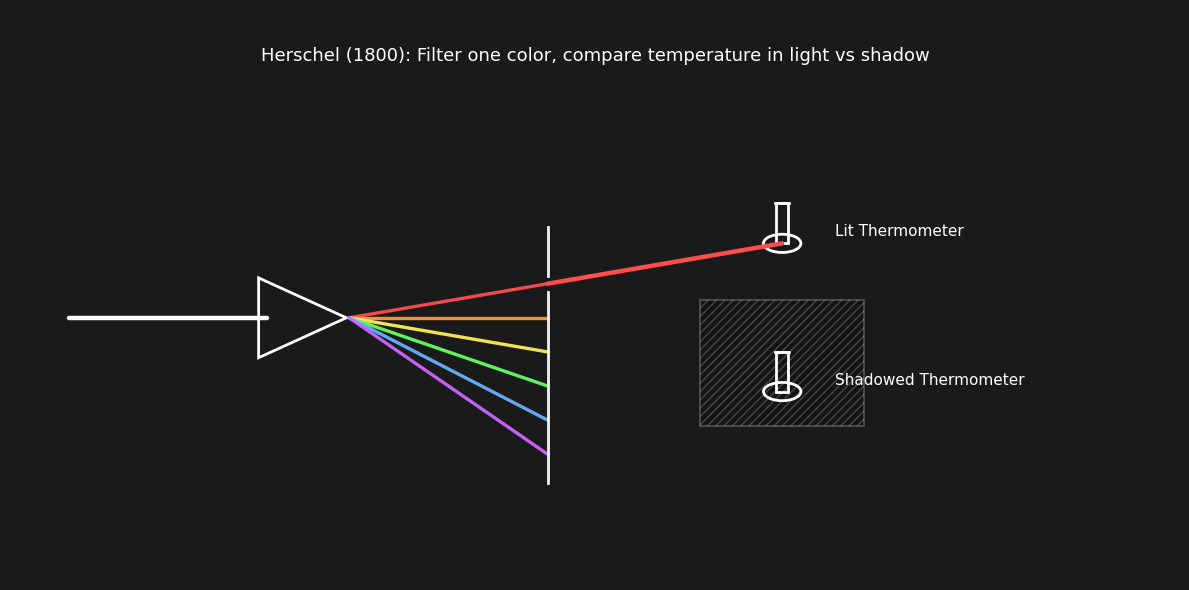

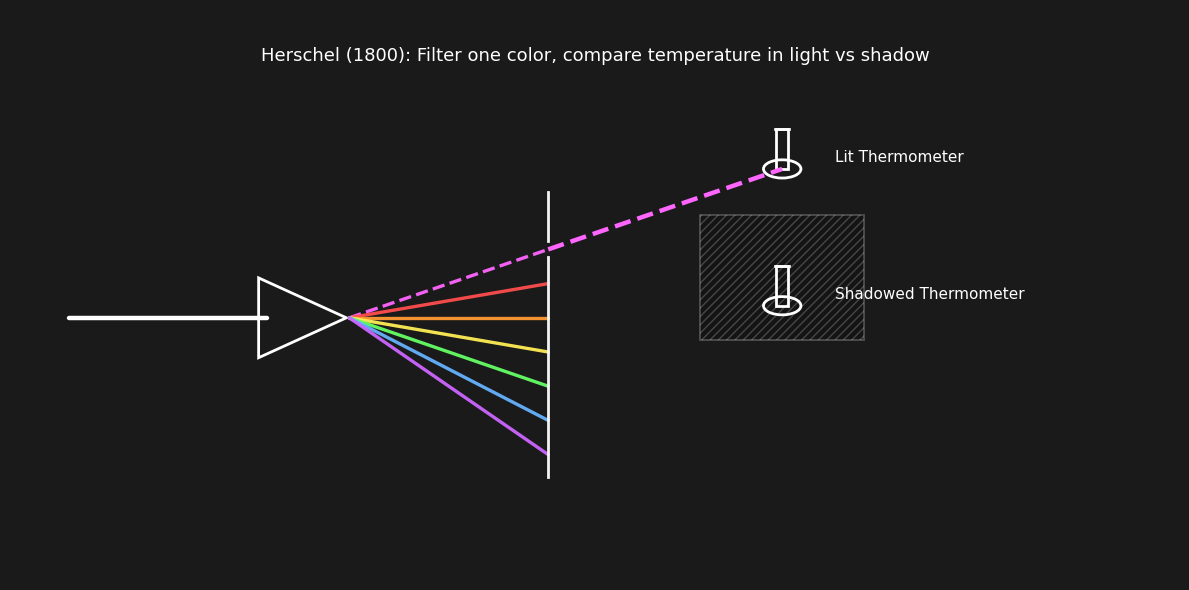

Herschel measured temperature change under various parts of the visible spectrum

He noticed that the temperature was trending upward toward red

Placing the thermometer outside the visible spectrum still produced substatial change

Here is the graph herschel published in 1800. These are unit-less values on the Y axis, normalized against each other. This was new research in a field that was not yet well understood. In fact in the paper, he supposes that there are 1000 “rays” and is determining how many of them are blocked by a substance. The number of rays wasn’t important - he was just speaking in ratios. The “S” plot on the left represents heat, and the “R” plot on the right represents perceived brightness.

Here I’ve plotted something grounded with today’s understanding of light. It’s not a perfect match since I’m using an idealized source of light, and I’m not simulating sending the light through earth’s atmosphere.

But you can see the same trend that Hershel noticed. The character of light goes beyond what can be seen.

Christiaan Huygens (1600s) and Thomas Young (1801)

Herschel’s choice of the word “momentum” is interesting. It reflects that the prevailing view at the time was that light was made of particles, which Newton referred to as “corpuscles.”

During Newton’s time, it had already been proposed that light could be a wave rather than a particle. Christiaan Huygens, contemporary with Newton, had proposed that light behaved as waves, where each point on a wavefront creates new waves that propagate outward spherically (Huygens’ Principle). But this was the less popular theory — Newton’s corpuscular view dominated until the 1800s.

In 1801, Thomas Young performed the famous double slit experiment, which showed that light could produce interference patterns.

We are all familiar with how a disturbance in water produces a ripple, and how ripples that interact with each other can amplify or cancel each other out. This experiment showed that light, passed between two narrow slits, behaved similarly to water ripples on a pond.

I think some important details of this experiment get glossed over, so I want to spend a little more time talking about how waves behave.

The “wavefront” is the “leading edge” of the ripple, and while we often observe a wave and say that the wave is moving, what we are really observing is a chain reaction of a disturbance. Imagine being in a swimming pool, and a ball is floating just out of reach. You can still influence the movement of that ball by pushing the water towards the ball, which then pushes the ball. Wave propagation works a lot like this. It is not a singular object moving through space, it is a chain reaction of disturbance.

I think most of us will find interference of waves to be intuitive. Waves that intersect can amplify or cancel each other out. But this experiment also relies on diffraction, which is perhaps not as intuitive.

Diffraction has to do with the way that waves go around an obstruction. Here, you can see two examples. You can imagine if I place my source of waves very far away from a barrier, that they will be traveling nearly parallel with each other. This is a bit like sun shadows in a game, where we assume the sun is so far from us that the light is traveling in a parallel direction.

On the left, when the gap in the barrier is comparable to or smaller than the size of the wavelength. We get a very wide diffraction. In fact, it acts increasingly like a point source with reduced intensity.

On the right, the gap is greater than the wavelength, so the central portion of the wave passes through the gap unaffected. However, even for a large gap there will still be some diffraction at both edges of the opening.

“Diffraction” is a behavior that applies to mechanical disturbances like water waves or sound waves. And it applies to electromagnetic disturbances like radio waves or light waves.

One of Newton’s arguments against light being a wave was that light doesn’t appear to diffract around surfaces the way sound or water waves do. It actually does! It is just very difficult to measure it because the wavelength of visible light is very short, less than a micrometer.

For the double slit experiment to work with visible light, ideally you’d want the slits to be less than 1/10 of a millimeter wide, and the slits to be less than 1mm apart.

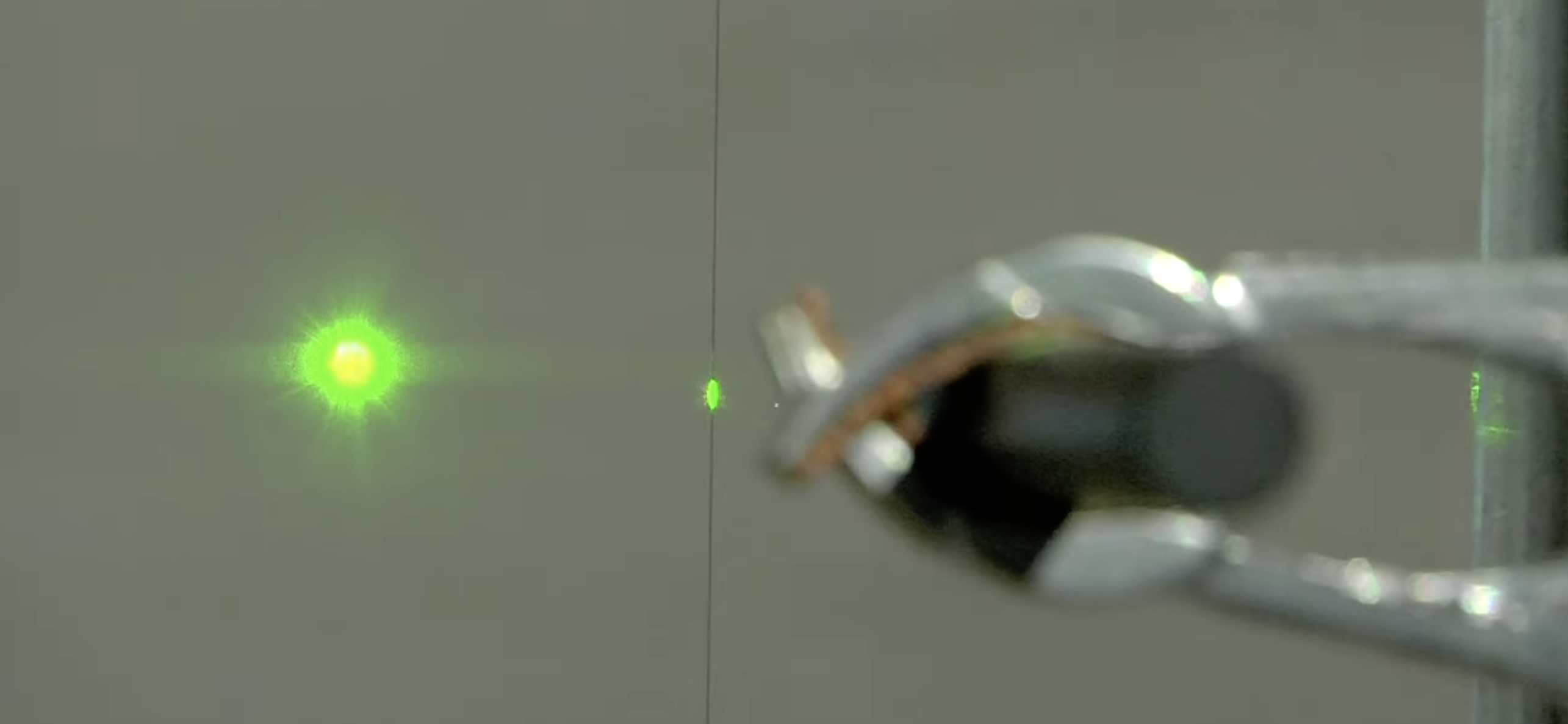

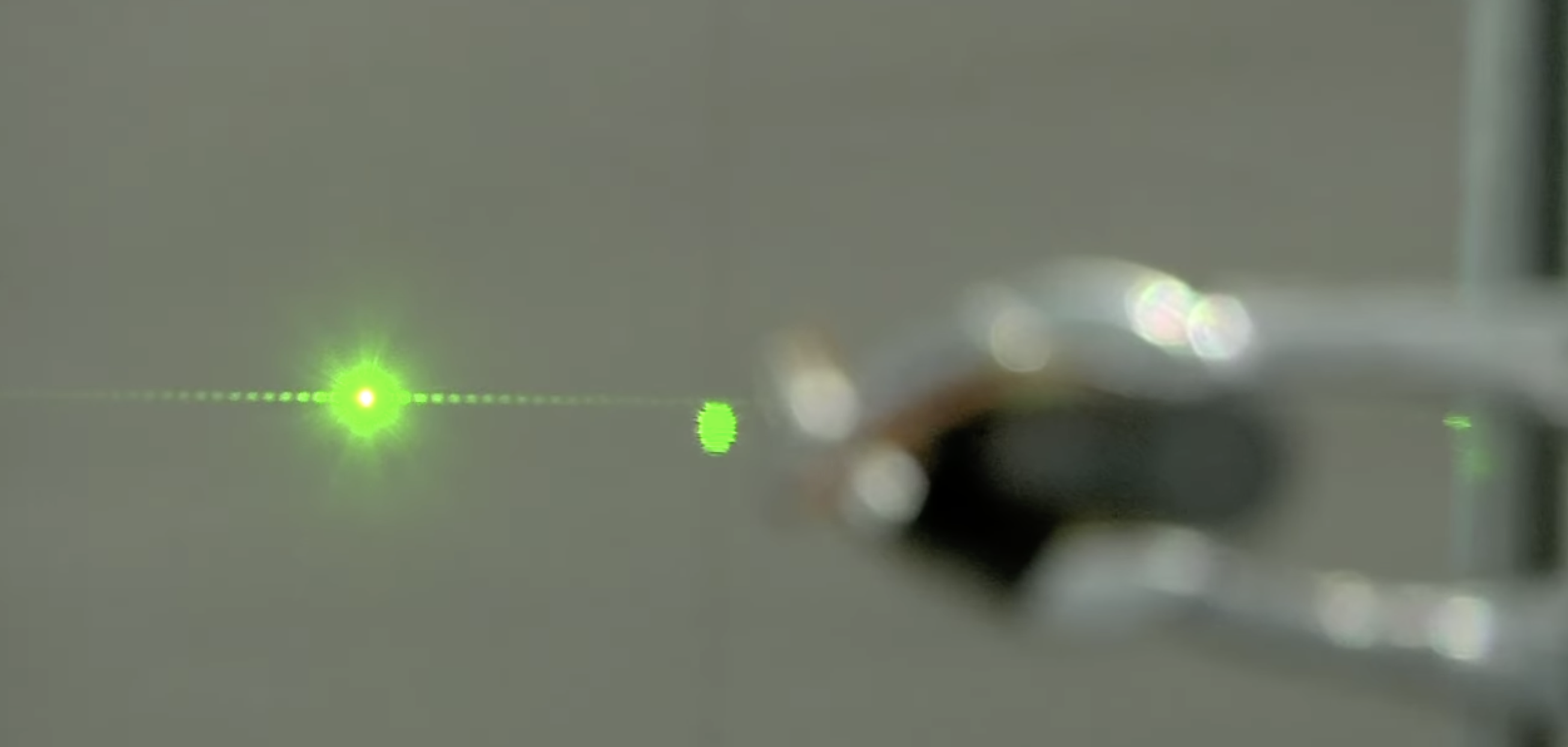

Here are some images of a slightly different experiment, where a thin wire is placed in the path of a laser. You would probably expect to see the wire cast a shadow. But this isn’t what happens - instead there is a bright point of light with no evidence of a shadow, and this odd line of constructive and destructive interference patterns.

Institute of Physics. Demonstrating diffraction using laser light – for teachers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71Rp-jG6Eek

The light is diffracting around the wire, and then acting in some way like water waves, canceling and amplifying. The double slit experiment was compelling evidence that led 1800s science to view light as a wave rather than a particle.

Institute of Physics. Demonstrating diffraction using laser light – for teachers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71Rp-jG6Eek

James Clerk Maxwell (1860s)

In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell proposed the famous “Maxwell’s equations” that unified electricity and magnetism. These equations predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves, and that they would travel at about 3.0x10^8 m/s.

The speed of light had been experimentally measured by this time, and the measured number aligned remarkably well with Maxwell’s prediction. Because of this, Maxwell proposed that light is a form of electromagnetic radiation.

Experiments a few decades later by Hertz confirmed the existence of these waves, and demonstrated that they behaved remarkably similarly to visible light.

Electromagnetic Spectrum

The discovery of the electromagnetic spectrum was nothing short of revolutionary, and I’m going to digress for a bit from the historical narrative to discuss it in more detail.

Many of you have likely seen a diagram like this before. On the left we have electromagnetic radiation with long wavelengths and low frequencies. Most of the world uses AC electricity that oscillates at 50 or 60 hz.

The wavelength is just speed of light divided by the frequency. So elecromagetic radiation can be described either way, and it implies the other. For example, the wavelength of 60hz is about 5000km.

Next, we move on to radio waves. To produce radio waves, we perform a similar oscillation with electrons on a wire, just at a much higher frequency. FM radio would be at about 100Mhz, or about 3 meters wavelength. Wifi, typically at 2.4Ghz or 5Ghz is a wavelength of about 12cm or 6cm. A very popular antenna design is a “quarter dipole” antenna - which is roughly one quarter of the wavelength. Incidentally, you can make an effective 2.4ghz antenna with a wire about 3cm long.

Recall the earlier analogy about being in a swimming pool and trying to push a nearby floating ball without touching it. Moving electrons around to create an electromagnetic wave is a bit like pushing water. These waves can then cause electrons on a wire somewhere else to move around. This is the gist of how radio waves work, although it might be a bit better to say we make electrons wiggle, or accelerate in different directions, 100 million times a second for an FM radio signal.

Wiggling electrons makes a wave. Then that wave propagates and causes electrons somewhere else to wiggle.

Another way to produce electromagnetic waves is to make something very hot. Before we discussed using electricity to wiggle electrons around in an organized, controlled pattern. But with enough heat, we can excite the atoms and molecules in the material, which causes electrons to vibrate and accelerate chaotically. This motion produces electromagnetic radiation across a wide range of frequencies.

You’ve seen this yourself if you’ve ever used a space heater. We run electricity through a wire, and make it hot enough that it produces infrared and visible electromagnetic radiation. A fire does the same thing - except the heat is produced through chemical reaction.

From https://rvelectricity.substack.com/p/portable-space-heater-dangers-f14

From https://rvelectricity.substack.com/p/portable-space-heater-dangers-f14

You probably already know that the hottest part of a fire is where the flames are blue. Blue light is an even higher frequency - meaning more energy and more heat.

(From https://roadville.com/blue-canoe/your-ultimate-guide-to-building-a-campfire/)

(From https://roadville.com/blue-canoe/your-ultimate-guide-to-building-a-campfire/)

Visible light is in the 100s of terahertz range, a wavelength of about half of a micrometer, or about half the thickness of a strand of spider silk. Very small, but not unthinkably small.

And we can continue increasing the frequency of the electromagnetic radiation past what we can see - onward to x-rays, gamma rays, and cosmic radiation.

The band of electromagnetic radiation that we can see is actually very narrow - less than a single octave. Whereas the sound produced by a piano covers about 7 octaves. We really have a very limited “view” of the electromagnetic spectrum with our eyes.

All of these effects come from changing a single variable - the frequency of the wave. (And frequency determines wavelength, so we can think of it that way too.) Whether it’s radio waves or visible light, they’re all electromagnetic waves that propagate in the same way - just at different frequencies.

Planck/Einstein (1900-1905)

By the 1900s, light was unquestionably considered a wave that radiates spherically. While no single experiment definitively proved light was electromagnetic, the evidence was overwhelming.

But two observations challenged classical wave theory:

First, classical physics didn’t accurately explain how hot objects emit light. In fact, they predicted that a hot object should emit infinite energy at high frequencies, which is absurd.

Second, observations around the photoelectric effect weren’t well explained.

The photoelectric effect occurs when light shines on a metal surface and ejects electrons from it. Classical wave theory predicted that brighter light—regardless of color—should always eject electrons with more energy.

But it was observed that dim violet light could eject electrons, while bright red light could not. It seemed dependent on frequency rather than brightness.

You can think of the electrons being “stuck” in a “potential well”. In order to escape, they need a big enough push. Classical wave physics suggested that bright light waves had higher amplitude, and the size of amplitude of the wave determined the size of the “push”. The model we use today recognizes the wavelength as the determinant of the energy of a photon, so increasing the “push” requires shorter wavelengths. Bright light is simply “more photons”.

Specifically, the formula is E = hf, where h is Planck’s constant and f is the frequency.

The solution to both problems ultimately required abandoning the idea that light is purely a wave. Max Planck proposed in 1900 that hot objects emit light only in discrete packets of energy, or “quanta”, to resolve the absurd predictions around how hot objects emit light. Einstein extended this idea in 1905, proposing that light itself travels as individual packets - later called “photons” - to explain the photoelectric effect.

This was deeply controversial. But an answer emerged gradually through the 1920s. Today, we accept that light is neither purely a wave nor purely a particle, but something more fundamental.

Generally speaking, for electromagnetic radiation at low frequencies, like radio waves, the wave-like behavior is more prominent. And for higher-frequency radiation like x-rays, the particle-like behavior is much more apparent.

Visible light sits somewhere in the middle where we can observe both the wave-like and particle-like behaviors.

While a photon can be like a wave, or like a particle, depending on how we observe it, it is really a photon. It acts like a photon.

It’s tempting to simplify photons by comparing them to familiar things like waves or particles. This can be helpful, and we will certainly be doing just that in the remainder of this talk. But analogies like this break down when pushed too far.

Ultimately, this quantum view of light also revolutionized our understanding of atoms. An electron in stable orbit around a nucleus creates a standing wave - the wavelength must be a multiple of the orbit’s circumference. This means electrons can only occupy specific energy levels, and when they jump between levels, they emit or absorb photons of specific frequencies - which is why heated elements emit characteristic colors in the form of electromagnetic disturbance.

The quantum interpretation is remarkably elegant, explaining a vast array of physical phenomena with shockingly simple rules. But it is a bit mind-bending, and all we were really looking for was the ability to reproduce a color. The good news is that for our purposes, we can almost always treat light as a particle with a wavelength. This point of view is accurate enough for most purposes.

So what is light?

- Light is electromagnetic radiation

- Light exhibits properties of both waves and particles

- We can think of light as consisting of photons - discrete packets of energy

- Each photon has a wavelength, which determines the color we perceive

- Visible light ranges from ~380nm (violet) to ~780nm (red)

- Photons can reflect off surfaces, be absorbed by materials, refract (or bend) when passing between materials, and diffract around barriers. Although diffraction isn’t typically apparent.

- Generally when rendering an image, ray-tracing approaches work great! Although there are some cases where refraction and interference must be considered to mimic a real-world effect.

For example, these soap bubbles show interesting patterns of color. Light bouncing off the “front” of the film is interfering with light bouncing off of the “back” of the film. This is an example of thin-film interference.

It happens because the wall of the soap bubble is similar to the wavelength of visible light, which ranges from about 0.4um to 0.7um. The wavelength of light is small, but not intagible!

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-physics/chapter/27-7-thin-film-interference/, credit: Scott Robinson, Flickr

Now we will move on to Part 2: Human Vision System!

References

- Newton’s experiments, well-explained here: https://youtu.be/--b1F6jUx44?si=wG2uUF_k9i7gFQBO

- 1800 paper from Herschel: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/rstl/article/doi/10.1098/rstl.1800.0020/121258/XIX-Experiments-on-the-solar-and-on-the

- Maxwell’s prediction of lights as electromagnetic spectrum: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Madera_Community_College/Concepts_of_Physical_Science/09:_Electromagnetic_Radiation_and_Optics/9.02:_Maxwells_Equations-_Electromagnetic_Waves_Predicted_and_Observed

- About Planck/Einstein, early quntum theory: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/University_of_Arkansas_Little_Rock/Chem_1402:_General_Chemistry_1_(Kattoum)/Text/6:_The_Structure_of_Atoms/6.2:_Quantization:_Planck,_Einstein,_Energy,_and_Photons

- I believe the analogy of waves being like pushing water comes from one of the feynman lectures on physics, but I don’t remember which one.

Image Credits

- Laser diffraction: “Institute of Physics”, “Demonstrating diffraction using laser light – for teachers”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71Rp-jG6Eek

- Space heater: https://rvelectricity.substack.com/p/portable-space-heater-dangers-f14

- Campfire: https://roadville.com/blue-canoe/your-ultimate-guide-to-building-a-campfire/

- Soap bubbles: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-physics/chapter/27-7-thin-film-interference/, Scott Robinson, Flickr